Directed by Brian De Palma

Sisters feels like a combination of old and new. The story itself, with themes of female suppression by male forces and a sense of grounded supernaturalism, feels very of the times in the 70s. The cinematography and music, on the other hand, feel steeped in old school techniques, including the familiar Hitchcockian music of Bernard Herrmann as well as a scene straight out of Rear Window.

The film even switches protagonists after act 1, much like in Hitchcock’s Psycho. The man through whom we enter the story, Philip (Lisle Wilson), is killed by one of the “sisters,” and suddenly our hero is the woman next door, an investigative journalist named Grace (Jennifer Salt) who struggles to be taken seriously, in part because the crime she witnessed is so meticulously covered up and because the police officers who respond to the call have disdain for her due to a few articles she wrote critiquing them.

Between Grace’s unfair punishment, first by the cops and later by the doctors who hypnotize her, as well as Philip’s (who happens to be black) murder, it is made clear that the (villainous) powers that be are white-male dominated. The police form one power structure while the clinic which once separated two siamese twins (the sisters) forms the other.

As Grace quickly jumps into her investigation, she fights both of these powers and runs into a huge brick wall when a creepy, mysterious man who turns out to be the doctor that separated the twin sisters (one of whom Grace is investigating for murder) convinces Grace that she herself is the evil twin.

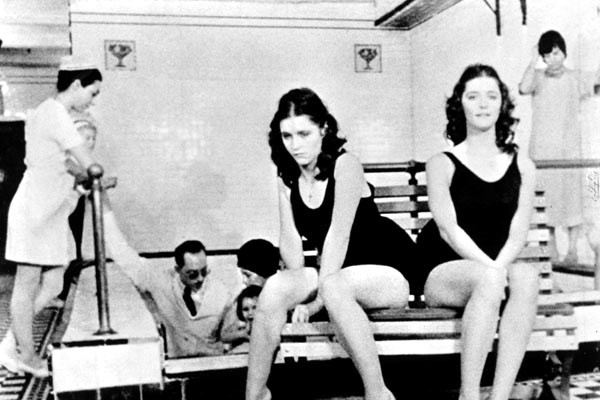

So to back up a little, we’re introduced to a young man, Philip, and a young woman, Danielle (Margot Kidder) as they go on an innocent date following a game show appearance. The gameshow is about peeping toms, and it immediately and effectively sets up a scenario in which we are already endeared to both parties in the young couple. Their date is tender and sweet, and we root for them even more when the woman’s ex-husband, Emil (William Finley) keeps showing up, having been stalking her for sometime now.

Eventually the couple sleeps together, and in the morning, the woman’s evil twin, Dominique, kills Philip. That’s when we learn that Emil was also the doctor who separated Danielle from Dominique. It’s unclear if he was stalking her due to jealousy or because he wanted to protect her.

The first act then, is so sweet, but it takes a hard turn. The good will was all a build up to the gleeful gore of the Philip’s murder, coupled with Herrman’s score. His death is tragic in a familiar Hitchcock kind of way. The tension works effectively because we’ve been given enough warning that something is up with this woman, and all that tension explodes in a pretty horrific death scene.

The rest of the film is more of a detective story in which we think we have all the information and are simply watching Grace play catch up. But as the story progresses, we’re given reason to doubt ourselves just as Grace begins to doubt herself.

In the second and third acts of this film, we’re introduced to a character outside the heteronormative perspective, and the film goes to great lengths to make sure we feel like we’re inside her head, not just standing next to her on the street. We’re shown and told what she’s up against. She’s a struggling writer for a struggling publication, but she pours her heart and soul into her work, even though this displeases the subjects of her articles like the police. Even her mother is troubled by her line of work, basically pleading for her to do something sensible, like get married (She’s only 25, but this is the early 70s).

Grace is up against a lot, but she at least has her convictions… until that begins to slip too. When Grace shows up at the clinic at which the siamese twins were separated, the doctor, Emil, claims to have been expecting her. See, she might just be a patient after all, and all this murder stuff was just a part of her delusion.

At this point the film makes a pretty big statement about the place of women in a male-dominated world. Is Grace’s passion for her (struggling) career all just a delusion because it’s outside of what she’s expected to do?

Whether or not it is a delusion within the context of the film, the point is made. In a pretty striking and engaging sequence, we see other angles of an old black and white newsreel film about the separation of the siamese twins. In this sequence, Grace is presented to be the ‘other’ twin, Dominique, the one who committed the murder we witnessed at the end of act 1.

It seems like there’s no question that she is in fact the evil twin, and suddenly our relationship with Grace has completely transformed. First we were beside her, then we were in sync with her, and now we’re in opposition to her, to a degree. We may still root for her, but we’ve come to see that she has just imagined all this.

Except we saw it too, the murder. We saw it from our own perspective, not hers. Because we’re meant to doubt whether the murder even happened, it means we’re doubting not only Grace’s version of events but also Philip’s version of events from the beginning of the story. That means we’re casting aside the truths held by two people outside of the white, male-dominated worldview.

At the end, however, we glimpse the insanity shared between Danielle and her husband/doctor, whom she finally kills after a breakthrough. The film, at this point, again pivots and the climactic moment occurs outside of our protagonist, Grace. The whole time she just lays on a bed while her newly separated sister (though we learn they’re not really sisters) kills the doctor and, in a sense, breaks the spell.

So even when the tables turn and Grace’s story about the murder is proven to be correct, she remains powerless. When the police finally visit her, asking abut the murder and conceding that she was right, we see that the hypnosis the doctor practiced on her still remains, and she repeats the there was no murder, it was just a misunderstanding.

The police get worked up, believing this to be some sort of vendetta against them and their doubt, but this is what she believes now. It’s a tragic story, and Grace loses almost all of herself in the process.

The results of this story suggest a lot about the role of women in the world at the time (and the message is still important today). Grace is up against a brick wall from the beginning, and that doesn’t change by the end, even when the narrative is resolved. What changes the most, though, is the audience’s relationship to Grace. At the beginning we’re right there with her, but we’re given reason to doubt her story, and then, at the end, we know she’s right even as she doesn’t. It means we have empathy and understanding for her, and her fate is unjust. It’s a simple story construction, meant to make us identify with the main character, and that’s what most films go for (the ‘save the cat’ moment meant to make us like the protagonist), but then De Palma plays the audience, making us doubt ourselves and question our role to the protagonist not just in this film but in films in general. I believe he makes us doubt Grace’s story because he knows the audience wants to doubt her story, whether because of the implied drama or because she’s a character who only ever faces doubt and opposition so why shouldn’t the audience relationship be any different?