Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Have you seen Glengarry Glen Ross? It’s that sales movie where Alec Baldwin delivers that “always be closing” speech about hitting your numbers. From my experience the quote is often taken out of context. This is one hell of a motivated guy, but the people whom he’s speaking to, the main characters of the movie, are all a bunch of struggling, desperate salesmen. One of them is played by Jack Lemmon. He’s a desperate, old, slimy salesman, duping his customers and being duped by the people he works for. He reminds me of Gil from The Simpsons.

Picture that sweaty, nervous energy, and that’s the force that drives Akira Kurosawa’s Scandal.

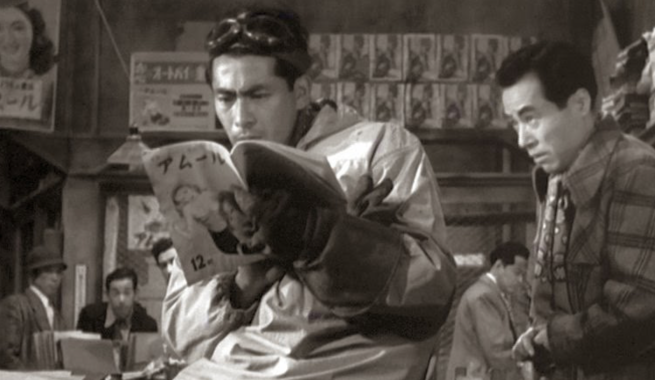

Hiruta (Takashi Shimura) is a lawyer who takes on a libel case, and in doing so he takes over the narrative from Ichiro (Toshiro Mifune), a young, handsome, ostensibly the leading man kind of character. Picture Brad Pitt circa 20 years ago, riding into the story on a Harley and looking like he’s about to court someone like Catherine Zeta Jones. It’s a love story, see, but when paparazzi photograph them together and publish the image under a headline saying they’re in love, Brad loses his mind, attacks the publisher and is then approached by Gil/Jack Lemmon to defend him in court.

It’s a court case movie, but when Hiruta enters the story, he takes complete control. As the legal representation, he holds all the power, and Ichiro follows his lead. But Ichiro, though drawn to the case for moral reasons, is quickly seduced by a higher offer to sabotage the case. He’s pretty open about the struggle this causes, suffering what appear to be multiple mental breakdowns.

And this isn’t the type of movie where he’s living double lives, pretending to represent his client while also working to undermine their own case. Hiruta is paid off by the opposition, the defendant in the lawsuit, and he just rolls over in court, playing his role so badly that everyone knows something’s up. The whole gallery cries foul, and Ichiro reveals to us that he too knows Hiruta is trying to destroy his own case. He just doesn’t know why.

Ichiro at first wanted little to do with Hiruta, but when he paid the man a visit and met the lawyer’s sick, pure of spirit daughter, he began to look at the man in a new light. She is a zen figure in the story, offering wisdom to anyone who asks and reminding everyone to settle the f*ck down. She tells her father directly that she knows he will destroy Ichiro’s case, and she tells Ichiro that her father is actively undermining him. What does Ichiro say? I know.

So this is a court case movie where the hero takes a bribe from his opposition. We expect him to redeem himself, and to some extent he does, but this isn’t a story full of suspense or plot twists. It’s really just a focus on a sad man who actively refers to himself as “a worm,” and whom everyone looks down upon. He’s a drunk, he’s a bad father presumably, he’s a shady lawyer, etc. and everyone just kind of tolerates it because they feel bad for him. Ichiro does at least, and I think we’re meant to follow his lead.

Ichiro Aoye is a celebrity within the world of a story, even if a minor one. He’s a painter whom some people recognize (the photo spread like wildfire because the woman he was with is a famous actress), but he rides his motorcycle everywhere, with the roar of the engine preceding his arrival like some ceremonious, regal horn players. He’s like a cowboy and the motorcycle his horse. People admire him, and he’s tall and handsome. For most of the movie he is side by side with Hiruta, and the juxtaposition between the two men is purposeful. One is tall, young, composed and the other is old, drunk and most likely ranting and raving.

Because Ichiro has such empathy for his dirty lawyer, then we do too. We’re also just so privy to his intense guilt that it’s hard not to feel for the man. He wears his emotions on his sleeve, but his constant outbursts quickly wear thin as he continues to mourn his own behavior but does nothing to change it.

So this is a strange story. Our hero is frustrating for most of the film until he finally turns it around, but even then that decision takes place so far into the movie that we have little time to live with the redeemed Hiruta.

His opposition is an unlikeable publisher, and the whole story takes a pretty hard stance on the paparazzi, chastising the way they use freedom of the press to so blatantly spread lies. Kurosawa apparently made the film in response to such paparazzi magazines that popped up after changes in censorship laws following the end of World War II.

So he makes this film to shine a light on an industry he finds disgraceful, and yet he chooses a hero who is seduced by that opposition. Sure, Ichiro is that idealized hero, but again he’s powerless, only present in the story to show the kind of people who can be harmed by such publication. Hiruta is the active character, but he’s wounded and quickly under the spell of the opposition.

Is the story meant to show the way systems fail us in general? Ichiro delivers a speech near the end of the film in which he asks if it was a mistake to put his trust in the judicial system. He has been harassed by the press and then wrung out by the court system.

It’s quite possible I’m over-analyzing all of this. If this wasn’t a Kurosawa film, and if there were no interesting historical considerations in regards to the culture in which the film was made, I might write Scandal off. It’s one of many courtroom dramas, though I’m not sure where that ‘genre’ was at when this was made. It’s melodramatic, and Hiruta’s loud performance might wear thin more quickly on some viewers.

At the sane time, I enjoyed the possible over-acting of his character. He’s tortured, just like other characters in early Kurosawa films. The actor, Takashi Shimura, played important roles in two previous Kurosawa films, Drunken Angel and Stray Dog. While there is some overlap with the character in those stories, he plays someone with much more composure and wisdom than he does here. The casting might be deliberate, like making good guy Henry Fonda the villain in Spaghetti Western. Because audiences at the time might’ve brought their own assumptions of the performer into the viewing, they assume he’s going to be more of a conventional hero.

But all the wisdom in Scandal comes from the youth, namely his daughter. She has been bedridden for five years and says it’s not so bad. She observes all the activity around her, weather flowers blooming or clouds overhead. She has achieve a certain peace that stands out all the more because of the chaos around her.

The world of Scandal is quite unlike the worlds of any of Kurosawa’s previous films. There is more activity, more energy. In other films we’re made to know all the characters who matter to a story. That might be just two lovers or a small gang of members of the yakuza. Either way we get a sense that the world of the story revolves only around these characters, like they live in their own bubble.

But in Scandal you get a sense of the broader, unseen world. That’s mostly because the work of the paparazzi is intended for that broader world, so this set up calls attention to all the things and people we cannot see. There is, in other words, an invisible mass of people in this story, and it just feels like, well I guess a normal world. We see the people who matter, but we’re well aware of all the life going on around us, even if we’ll never know it intimately.

This contrasts with those earlier Kurosawa films because you feel that everything that matters, everyone that matters, is right in front of you. There might as well not be a world outside of the central characters’ story. Those films have the feel of a bottle episode of tv, something self-contained, even as they’re set amongst crowded villages.

So maybe Scandal just feels more modern than those other stories. It at least feels more conventional, like the setting is borrowed from real life rather than pulled from deep within Kurosawa’s soul. To attempt to describe it one more time, it’s like the entire creation of those other films was ripped from Kurosawa’s mind. The way he saw the city, the people, etc. all felt of a singular tone of voice. It was subjective, and it was a representation of what he saw. Scandal, on the other hand, has distinctive Kurosawa touches, but it’s as if he was brought into the process when the story was already halfway written.

Up Next: On Dangerous Ground (1951), The Spiral Staircase (1946), Spellbound (1945)